BLUF Statement (Bottom Line Up Front)

It was previously believed that long-term smoking cessation results in normalization of lung cancer risk; unfortunately, examination of the very large data set provided by the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II (CPSII) revealed that while smoking cessation is beneficial at any age, risk reduction is far less than complete. This article provides the simple methodology for calculating persistent risk of lung cancer in long-term ex-smokers.

Cancer Prevention Study II (CPSII)

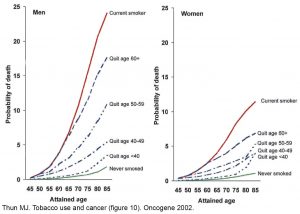

In March 1993 Halpern and co-workers published a study titled “Patterns of absolute risk of lung cancer mortality in former smokers” in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. This study resulted from analysis of more than 850,000 Americans living in all 50 states who participated in the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II (CPSII). Halpern reported the number of deaths per years of life in 196,529 current smokers, 212,050 former smokers and 444,210 never smokers and also stated the relative risk of lung cancer death in former smokers who quit at different ages, compared to (i.e. relative to) the risk of lung cancer death in current smokers. Updated CPSII data was reported in 2002 by Thun et al of the Department of Epidemiology of the American Cancer Society and was further validated in 2004 by Sir Richard Doll et al who published an extraordinary report, a 50-year follow-up study of cigarette smokers that was started in 1951. Sir Richard (October 28, 1912 – July 24, 2005) and Sir Bradford Hill (July 8, 1897 – April 18, 1991) were among the first to suggest, in a study published in the British Medical Journal in 1950, that a cause and effect relationship existed between cigarette smoking and lung cancer.

Example of risk calculations using a table derived from the CPSII data

Consider the example of a man who started smoking cigarettes at age 17 and continued to smoke until age 55. At age 70, 15 years after smoking cessation, the patient was found to be suffering from a large right upper lobe lung cancer. Despite surgery and chemotherapy, the patient’s condition deteriorated and he succumbed at age 71.

Many medical experts continue to testify that the risk of lung cancer is eliminated, or is almost eliminated, after 13 years of smoking abstinence. Let us see if that is true: look at the table below which I prepared from data provided by Halpern et al (page 462). Go across the first row (“Age”) to the column “69-73”, that is, the age range for when the patient in our example died. Then go down that column to the “55-59” row, that is, the age when the patient stopped smoking. In the cell at the intersection of the “69-73” age at death column and the “55-59” age at quitting row are 3 numbers: (1) 23,664 which is the total number of years of life among the patients identified by Halpern who had stopped smoking at age 55-59; (2) 64 which is the number of those patients who died of lung cancer and (3) 270.45 which is the lung cancer mortality rate per 100,000 per year [(64/23,664) x 100,000].

Let us further consider the risks of lung cancer mortality exposed by Halpern’s analysis of the CPSII data: Halpern identified 23,664 person-years in individuals who stopped smoking between the ages of 55-59 and were still alive at 69-73. The lung cancer mortality rate for 69-73 year old people who quit smoking between 55-59 was 270.45/100,000 per year. The latter represents a substantial improvement compared to the number of deaths in ongoing smokers 69-73 which was 643.01 per 100,000 per year (third row of the table) but among the never smokers aged 59-63 (second row of the table) there were only 91 lung cancer deaths in 291,341 person-years or 31.23/100,000 per year.

The risk of lung cancer death attributable to smoking for a person 69-73 years old who quit smoking at some time between 55-59 can be compared “relative to” the risk of lung cancer death attributable to smoking for a person 69-73 years old who continues to smoke, as follows (note that 31 is the annual lung cancer death rate per 100,000 among never smokers 69-73 years old and therefore, is the “background” rate for that age group).

(271-31)/(643-31)

= 240/612

= 0.39

This is good and represents the benefit or “risk reduction” of 61% achieved by smoking cessation for such patients; however, the risk of lung cancer death attributable to smoking for a person 69-73 years old who quit smoking at some time between 55-59 should also be compared “relative to” the risk of lung cancer death for a person 69-73 years old who never smoked, as follows:

(271-31)/31

= 240/31

= 7.74

= 774% greater risk of lung cancer death attributable to smoking for a 69-73 year old ex-smoker who quit at 55-59 compared to 69-73 year old never smokers. Furthermore, the simple lung cancer mortality risk ratio (compared to never smokers) for a person 69-73 years old who quit smoking between 55-59 is:

271/31

= 8.74

= 874% greater risk of lung cancer death.

Medical-legal implications of the persistent risk of lung cancer death

Defense tobacco attorneys (and witnesses) and plaintiff asbestos attorneys (and witnesses) have argued, incorrectly, that long duration (>10 or 15 years) of smoking cessation eliminates all or almost all the risk of lung cancer in former smokers. In tobacco trials, it has been suggested that a lung cancer which arose in a long-term ex-smoker must have been caused by something other than smoking. In asbestos trials, it has been suggested that a lung cancer arising many years after the patient stopped smoking must have been caused by asbestos exposure (no matter how minimal) because smoking was not the cause. In fact, cigarette smoking is the cause of most lung cancers, not only in current smokers but also in former smokers.

Smoking cessation at any age is very valuable because it significantly improves health and decreases the risk of cigarette-induced diseases, but only very early smoking cessation (by about age 30) results in nearly complete elimination of cigarette-induced lung cancer risk. The reader is reminded that risk and event are two different things. A patient who has accumulated a great deal of lung cancer risk because of smoking into old age may live out his years without ever developing a lung cancer (he may die of another cigarette-related disease such as myocardial infarction or stroke or he may die of a disease unrelated to smoking). Another patient who stopped smoking in middle life, and by so doing eliminated most of his lung cancer risk, may end up dying of lung cancer. The table below can be used to calculate persistent lung cancer risk after smoking cessation.

| Person-years of exposure, lung cancer deaths and lung cancer mortality rate/100,000 based on Table 4 (appendix) Halpern et al JNCI 1993 | ||||||||

| Age | 40-43 | 44-48 | 49-53 | 54-58 | 59-63 | 64-68 | 69-73 | 74-80 |

| Never smoker | 82,335 | 248,278 | 426,334 | 475,964 | 466,829 | 394,931 | 291,341 | 235,547 |

| 0 | -9 | -20 | -33 | -61 | -75 | -91 | -93 | |

| 0 | 3.63 | 4.69 | 6.93 | 13.07 | 18.99 | 31.23 | 39.48 | |

| Current smokers | 46,626 | 135,527 | 237,120 | 253,832 | 217,673 | 144,344 | 80,558 | 38,664 |

| -5 | -62 | -195 | -398 | -592 | -622 | -518 | -332 | |

| 10.72 | 45.75 | 82.24 | 156.8 | 271.97 | 430.92 | 643.01 | 858.68 | |

| Former smokers | ||||||||

| Age at cessation | ||||||||

| 30-39 | – | 51,741 | 97,504 | 97,499 | 67,401 | 38,332 | 20,440 | 9,354 |

| -4 | -18 | -27 | -13 | -22 | -14 | -4 | ||

| 7.73 | 18.46 | 27.69 | 19.29 | 57.39 | 68.49 | 42.76 | ||

| 40-49 | – | – | – | 101,504 | 100,555 | 67,433 | 34,810 | 17,478 |

| -53 | -74 | -72 | -38 | -20 | ||||

| 52.21 | 73.59 | 106.76 | 109.96 | 114.43 | ||||

| 50-54 | – | – | – | – | 48,969 | 40,362 | 26,326 | 13,667 |

| -66 | -54 | -45 | -33 | |||||

| 134.78 | 133.79 | 170.93 | 241.46 | |||||

| 55-59 | – | – | – | – | – | 36,474 | 23,664 | 13,576 |

| -89 | -64 | -48 | ||||||

| 244.01 | 270.45 | 353.57 | ||||||

| 60-64 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 24,436 | 15,971 |

| -100 | -97 | |||||||

| 409.23 | 607.35 | |||||||

| 65-69 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12,555 |

| -91 | ||||||||

| 724.81 | ||||||||

Appendix: Thun 2002 Tobacco Epidemiology (click image for larger version)

[1]. Halpern, MT, Gillespie BW, Warner, KE: Patterns of absolute risk of lung cancer mortality in former smokers. J Nat Cancer Inst 1993; 85:457-464. [2]. Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Calle EE. Tobacco use and cancer: an epidemiologic perspective for geneticists. Oncogene 2002; 21, 7307-7325. [3]. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004 Jun 26;328(7455):1519.